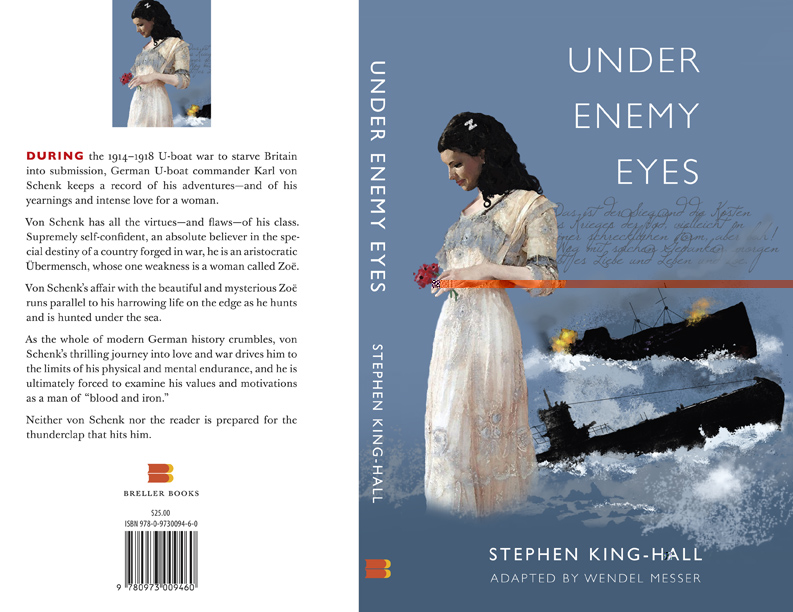

Under Enemy Eyes

Stephen King-Hall

Diary of a U-boat Commander

This book was first published under the title Diary of a U-boat Commander .The date of publication of the first edition is unknown. The title page of the original edition, published by Hutchinson & Co., gives no date; and Random House, the present owners of Hutchinson, have no date on record. It first saw the light of day soon after the end of the First World War, most likely in 1919.

The Author

The Author, Sir William Stephen Richard King-Hall, Baron King-Hall of Headley (1893 - 1966) was educated at Lausanne, Switzerland, and at the Royal Naval College in Dartmouth. He fought in the First World War with the Grand Fleet, serving on HMS Southhampton, and with the 11th Submarine Flotilla. He was awarded the gold medal of the Royal Institute of International Affairs for his 1920 thesis on submarine warfare. During the Second World War, he served in the Ministry of Aircraft Production as Director of Factory Defence. In 1944 he founded and chaired the Hansard Society to promote parliamentary democracy. He was created Baron King-Hall in 1966.

The U-boat Diaries

This book is, in part, based on written records found in a u-boat

by King-Hall himself, as he had the task of receiving surrendered U-boats

at Harwich in November, 1918.

In one of them he found diaries of the commander.

The Admiralty told King-Hall to throw them into the sea, but he took them home

and had the idea of writing a novel. He used the nom de plume “Etienne”

because naval officers were not permitted to publish.

Back Cover Résumé

During the 1914-1918 U-boat war to starve Britain into submission, German

U-boat commander Karl von Schenk keeps a record of his adventures — and of

his yearnings and intense love for a woman.

Von Schenk has all the virtues — and flaws — of his class. Supremely self-

confident, an absolute believer in the special destiny of a country forged

in war, he is an aristocratic Ubermensch, whose one weakness is a woman

called Zoe.

Von Schenk’s affair with the beautiful and mysterious Zoë runs

parallel to his harrowing life on the edge as he hunts and is hunted

under the sea.

As the whole of modern German history crumbles, von Schenk’s thrilling

journey into love and war drives him to the limits of his physical and mental

endurance.

Neither von Schenk nor the reader is prepared for the thunderclap that

hits him.

Author’s Introduction

“I would ask you a favour,” said the German captain, as we sat in the cabin

of a U-boat which had just been added to the long line of bedraggled captives

that stretched themselves for a mile or more in Harwich Harbour, in November

1918.

I made no reply; I had just granted him a favour by allowing him to leave the

upper deck of the submarine, in order that he might await the motor launch in

some sort of privacy. Why should he ask for more?

Undeterred by my silence, he continued: “I have a great friend, Leutnant

zur See von Schenk, who brought U-122 over last week. He has lost a diary,

quite private. He left it in error. Can he please have it?”

I deliberated, felt a certain pity. But the fate of the Belgian Prince flashed

through my mind—the ship going down, the capture of the men in the lifeboats,

the lifeboats being destroyed, the abandoned crew left on the deck of the

U-boat as it submerged, the men drowning.

Looking the German in the face, I said:“There’s nothing I can do.”

“Please!”

I shook my head; then, to my astonishment, the German placed his head in his

hands and wept, his massive frame (for he was a very big man) shook in

irregular spasms. It was a most extraordinary spectacle.

It seemed to me absurd that a man who had suffered, without visible emotion,

the monstrous humiliation of handing over his command intact, should break down

over a trivial incident concerning a diary, and not even his own diary, and yet

here was this man crying openly before me.

It rather impressed me, and I felt a curious shyness at being present, as if I

had stumbled accidentally into some private recess of his mind. I closed the

cabin door, for I heard the voices of my crew approaching.

He wept for some time, perhaps ten minutes, and I wished very much to know of

what he was thinking, but I couldn’t imagine how it would be possible to find

out. I think that my behaviour in connection with his friend’s diary added the

last necessary drop of water to the floods of emotion which he had striven, and

striven successfully, to hold in check during the agony of handing over the

boat, and the despair of losing the war, and the defeat of all German ambition.

And now the dam had crumbled and broken away.

It struck me that, down in the brilliantly lit, stuffy little cabin, the result

of the war was epitomized. On the table were some instruments I had forbidden

him to remove, but which my first lieutenant had discovered in the engineer

officer’s bag. On the settee lay a cheap, imitation-leather suitcase, containing his spare

clothes and a few books. At the table sat Germany in defeat, weeping. Not the

tears of repentance, rather the tears of bitter regret for humiliations

undergone, and thwarted ambitions.

Here was the crumbling of the whole of modern German history. And I doubt not

that the cruelty of Captain Werner, who commanded the U-boat that destroyed

the Belgian Prince, leaving the merchant seamen to drown, was also motivated

by this same bitterness of defeat.

They had given their all, even over the generations, only to be put down,

defeated, humiliated.

No, this was not a time for pity.

We did not speak again. The launch came alongside, and, as she bumped against

the U-boat, the noise echoed through the hull into the cabin, and aroused him

from his sorrows. He wiped his eyes, and, with an attempt at his former

hardiness, he followed me on deck and boarded the motor launch.

Here then, translated from the German, is the diary this man requested, and

which I denied him — the Diary of Karl von Schenk.